I (Karma) first went to the Museum of London in 2006. On its grounds are the remains of the original Roman Wall.

The Roman Wall, from a 2007 trip

When Courtney and Liam suggested we go there this June, I was excited about the exhibition, London Nights. I quickly discovered, however, that the Museum had undergone a massive renovation since I’d last been there–it was much bigger, much grander, but still had its senses of wonder and humor.

This Museum tells the history of London itself, from its “prehistory” days through the Romans, the dark ages, the Enlightenment and the ages after.

London is a grand city, deserving of this grand museum.

I saw the Harry Potter play in this theatre, The Palace.

“Teddy Boys,” though they look like T-Birds to me.

London Nights is an amazing photography exhibit, featuring antique pictures of London at night, from the days of early photography from now. Our favorite sections were the oldest photos, the collection of pictures from the infamous Night Bus by Nick Turpin, and Damien Frost‘s photographs of London’s Drag Queens.

by Nick Turpin

by Damien Frost

The Museum also had a small exhibit about a current plague on the city–Fatbergs.

It is my sad duty to inform you that fatbergs are collections of solid toxic waste in sewers, clogging London and the developed world–the problem is exacerbated by our use of wipes instead of paper. They had dried samples at the museum, in layers of protective glass, to protect us from ourselves.

This exhibit is arguably one from the anthropocene–a newish term for our time, in which we acknowledge that humans have forever altered and harmed the Earth for our own purposes. The term is contentious, but it’s hard to disagree with its use when one encounters a fatberg.

After considering our waste, we retreated into the past to feel slightly better about ourselves, encountering

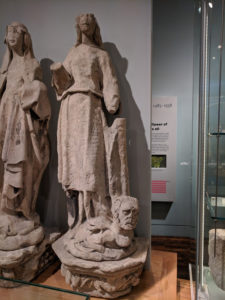

- statues of the cardinal virtues, standing on what I guess are demons–they certainly don’t like whatever is happening to them (the placard said who the virtues were, but nothing about the dudes they were balancing upon);

- a stylized re-creation of a Victorian-era pleasure garden*;

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

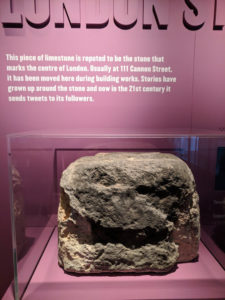

Singing of Mount Abora. - the famous London stone, which has a twitter account;

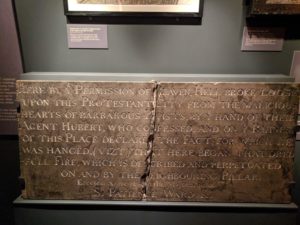

- an old “on this site” stone, about how they totally executed a patsy for the Great London Fire (this stone had to be removed had to be removed from the street in the mid-1700s–readers were causing “traffic jams”);

Bragging about scapegoating–Americans are definitely descended from these folks

- an exhibit on how they made the amazing opening of the 2012 London Paralympic Games;

some of the Olympic cones used to create the torch

and many other treasures.

Then, on our way to Nando’s, we stopped to take some pictures of and with St. Paul’s.

This obscenity is aimed at the photographer, dear reader.

St. Paul’s

Note: Like most UK museums, the museum was free–only the London Nights special exhibit required cash.

*Victorians were weird. They were in great denial about their obsession with sex. (Well, maybe not so weird. The South has the highest rates of sexual issues (unplanned pregnancies etc.) in the U.S., and Utah has the most porn searches, so hypocrisy is technically normal.)

They were big on gardens, nature, and pleasure, though, combining a burgeoning understanding of the natural world through science (this was the period where they named every damn kind of fern, remember) with the ability to talk about reproduction–in plants, at least.

In the UK, by the way, gardens are gardens, but they are also yards. And British people love them in all of their forms, as evidenced by this wonderful song by Laura Mvula.

Talk of the famous pleasure gardens (elaborate playgrounds for the rich) always reminds me of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan.”

Coleridge said he awoke from a dream and started writing the poem down in a fury, until he was interrupted by a knock on the door, causing the poem to be forever unfinished.

One of my professors once gave a lecture about how it’s a metaphor for writing. Khan calls forth the dome by fiat, like god creates, like writers write.

Go back and read it again.

I’ll wait.

The writer metaphor theory is sound.

My theory is equally sound, however.

As I have explained to several classes, this poem is about wet dreams.

Go read it again.

There’s a pleasure dome, with its sexy gardens and romantic chasms and references to sex with incubi. Hot Abyssinian maids . . . fast thick pants and mighty fountains: